The 1921 Railways Act and the Centenary of the 1923 'Big Four' Grouping

A Customer and Staff Perspective

Prior to 1923, the construction and operation of the railways was driven by private enterprise in a largely uncoordinated, heavily competitive and fragmented manner. By 1923, despite some consolidation, more than 120 railway operating companies were still in existence although many were unprofitable and struggling to compete with the development of road transport.

The Railways Act 1921, also known as the Grouping Act, was a UK Act of Parliament aimed to stem the losses by “grouping” 120 companies into the “Big Four”:

The act aimed to move the railways away from internal competition, and retain some of the benefits which the country had derived from a government-controlled railway during and after the Great War of 1914-1918.

The provisions of the Act took effect from the start of 1923.

Customer Impacts and Reaction

The Positives

The act resulted in improvements to the range and quality of services which were well received by customers. The types of improvement included:

- Frequency and choice of services: The new companies were able to run more trains and introduce new services, including new routes, generating more and better options for the travelling public when planning their journeys. Improvements were already being seen by August 1923 on the GWR in the frequency of services to the previously neglected Cambrian Coast. Similarly on the LMS and LNER new cross-country services were being introduced such as Penzance to Aberdeen and Liverpool to Yarmouth. Progress on the Southern was slower at that time due to the delay of the appointment of the General Managers although “One great boon already has been the interchangeability of tickets …. and through running such as the service from Dover to Bournemouth, which was not found possible before the group came into existence”.

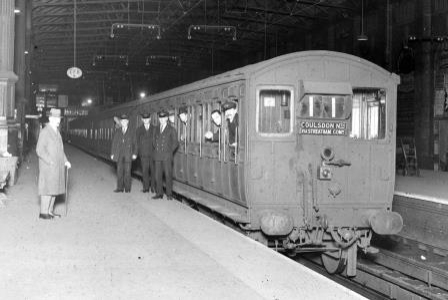

- Investment: The new groups invested heavily in new infrastructure, which improved the quality of the railway network. Perhaps nowhere was this more notable, better planned or efficiently executed than with the Southern Railway electrification scheme which increased train miles from a weekday average of 130,000 in 1923 to 170,000 by 1938 with a corresponding 12% reduction in passenger vehicles and staff reduction of 3,350. On a smaller scale, within a year of the Grouping, work was underway to improve Victoria station by making the two existing stations into one and similar was expected for London Bridge, though this was complicated by the two stations being on different levels.

- Punctuality and Reliability: Timetables could be better co-ordinated reducing connection times and the late running of trains. This and other factors made the new companies more reliable than the pre-grouping companies which in turn meant that passengers were less likely to experience delays or cancellations.

- Comfort: Investments were made in new rolling stock, which made for a more comfortable journey.

- Reduced fares: The new groups were able to achieve economies of scale and negotiate lower prices with suppliers, which they passed on to passengers in the form of lower fares.

- Safety: The new groups implemented new safety measures, which made the railways a safer place to travel.

- Customer service: The new groups were more responsive to customer feedback and complaints, which led to an improvement in the overall customer experience.

Customer Complaints

While the act was intended to modernize and streamline the railways with corresponding benefits for customers, it did have some negative effects. The companies placed greater focus on profit rather than investing in the maintenance and improvement of the infrastructure. This led to a decline in the quality of the railway network, resulting in slower and less reliable services.

The ‘Big Four’ had a near monopoly on rail travel in the UK and this lack of competition allowed them to increase prices without fear of losing customers to rival companies.

Furthermore, the consolidation of railway companies resulted in reduced connectivity between different parts of the country. Smaller railway lines that were not included in the ‘Big Four’ Grouping were sometimes shut down making it more difficult for people in rural areas to access rail serices.

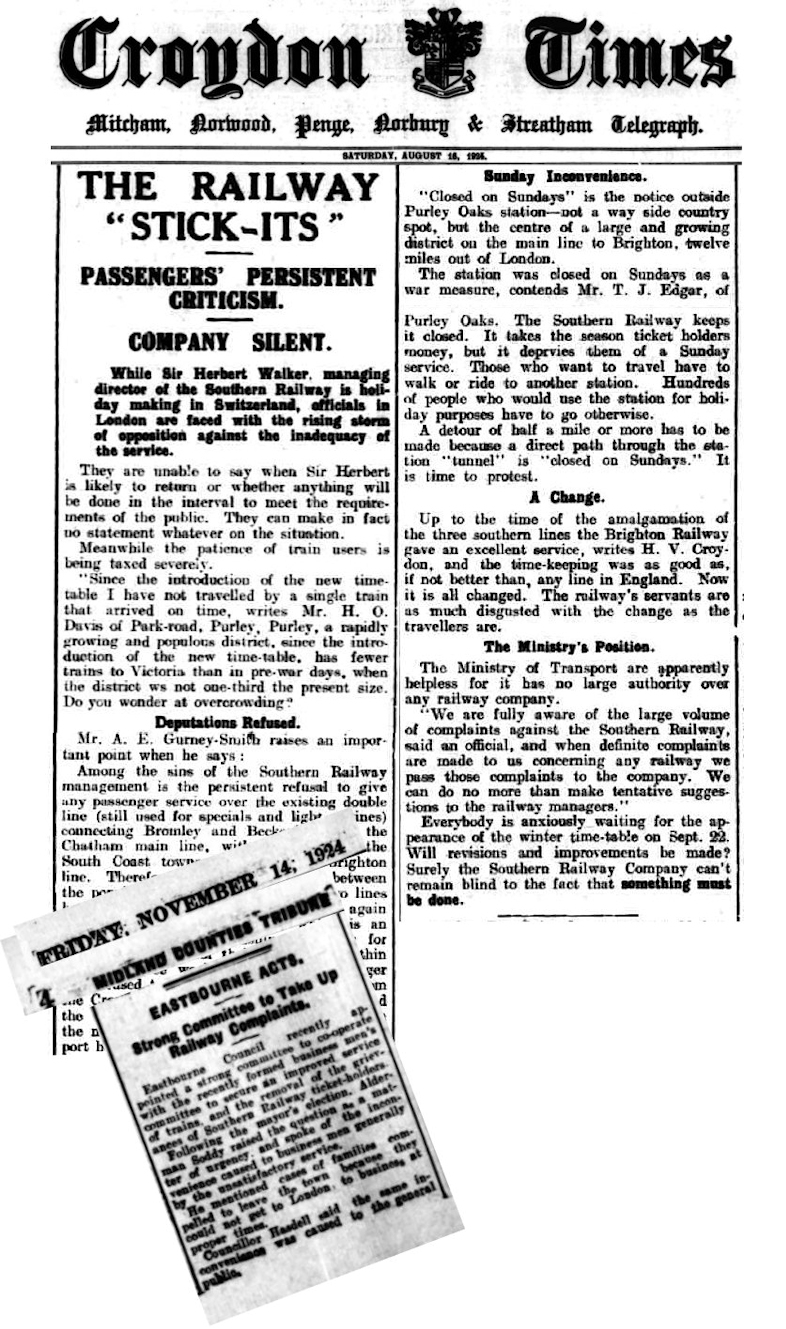

Some of the impacts on customers may have been temporary and/or a feature of the transition. There were serious problems with the Southern 1923 summer timetable and particularly with the concentration of services for Portsmouth on London Waterloo. Whilst this helped better manage the heavy holiday traffic, it came at the cost of reduced service levels on the alternative London Victoria route to places such as Chichester and Bognor. This was remedied in the subsequent winter timetable.

This led to the following types of customer complaints and concerns:

- Decline in the Quality of service: As can be seen in the Croydon Times above, there were customer complaints about trains being late, overcrowded, and dirty.

- Higher fares and lower quality of service due to a lack of competition: While fares did increase in the years following the introduction of the Railways Act, they did not rise to the extent that some had feared. In practice, the Act actually helped to create a more stable and consistent system of pricing across the industry, which made it easier for passengers to plan and budget their journeys. Nevertheless, concerns remained around the level of fares and competition throughout the 1920s and beyond.

- Reduction of choice: Customers complained that the grouping had led to a reduction in the number of train companies, which had reduced their choice of services.

- Poor communication: Customers complained they had not been given enough information about the changes arising from the transition.

- Reduced accountability: Customers felt there was no way for them to complain about the poor service or to get their money back.

- Less transparency: Customers said that they did not know how the railways were run or how their money was being spent.

- Lack of investment and innovation: Customers complained that a lack of investment and innovation was leading to delays, cancellations and a decline in the quality of service. In fact, £200 million was spent on capital investment in the decade after the Grouping, though mainly focused on equipment rather than railway stations.

- Reduced customer focus: Customers complained that the railways were more interested in making money than in providing a good service.

Impacts on and Reaction of the Railway Staff

Positives

The Grouping led to a number of positive outcomes for railway staff that were well received:

- Improved pay: The Act ensured that railway employees received better pay and pensions. This was important because railway employees had been poorly paid for years, and the Act helped to improve their standard of living.

- Better working conditions: The Act ensured better working conditions for railway employees, including shorter working hours and improved safety measures. The railway companies were required to provide better facilities for their employees, including accommodation, canteens, and welfare facilities.

- Increased job security: The Act allowed the railway companies to merge, which helped to create larger, more efficient and viable companies with less competition between companies. The larger companies were able to invest in new technologies and adopt the best methods and technologies from pre-grouping companies which made the railways better able to compete with road transport, ensuring the long-term viability of the industry. These factors led to greater job security for employees.

- Better training: The Act required railway companies to provide better training for their employees. This meant that railway workers were better equipped to handle the challenges of their jobs, and it also helped to reduce accidents and improve safety.

Employee Concerns

- Job losses were the main concern of the employees. Between 1922 and 1932 working expenses of the ‘Big 4’ fell by £49M and the majority of this reduction related to staff costs. The consolidation of many small railway companies resulted in the closure of some redundant facilities and the merging of job roles. This led to a significant reduction in the number of railway workers, widespread job losses and unemployment in the industry. Many railway workers also faced wage cuts and longer working hours as the new companies sought to reduce costs and increase efficiency. This had a profound impact on many communities across the country, particularly in rural areas where the railway was often the main source of employment.

- The act also removed many of the benefits that railway workers had previously enjoyed, such as free or discounted travel, and increased the retirement age. Workers also felt that their voices were not being heard in the decision-making process as the act gave more power to the new railway companies and their shareholders.

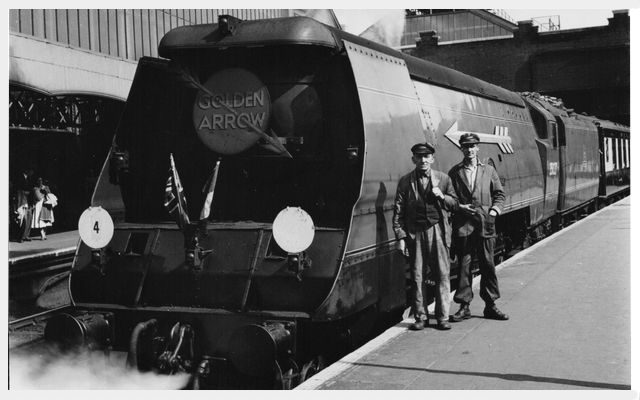

- With the new companies came new uniforms for railway staff. This was part of a wider effort to create a more professional and unified image for the railway system. While some workers welcomed the changes, others found them difficult to adjust to. The uniforms were often seen as a symbol of the wider change taking place in the railway system and some workers felt that they were losing their individuality and identity.

- Overall, the 1921 Railways Act was seen by many railway employees as a negative development that had a significant impact on their lives and livelihoods.

Conclusion

While the 1921 Railways Act aimed and was reasonably successful in modernising and streamlining the UK’s railways, it did have several negative effects that impacted customers, railway staff and rural communities. This was reflected in the mixed reaction of customers:-

“I have noticed a considerable improvement in the standard of service since the Railways Act was introduced. The new companies seem to be more efficient, and the staff are better trained and better equipped to deal with passengers.”

Others were not so happy. A frustrated colliery proprietor wrote that pits were having to work short time “owing to the inability of the amalgamated railway companies to handle the traffic and to provide empty wagons”.

The act highlights the importance of considering the wider impacts of legislation on various stakeholders and the need for balance between commercial interests and social responsibility.

Beyond Grouping

In 1938 the Rail Executive Committee (REC) which had run the railways during World War 1 was re-formed with a remit to run the countries railways if war broke out.

Management of the railways remained with the Big Four until 1939 when, shortly after war was declared, the REC took control.

REC control lasted until the railways were nationalised in 1948.